Over the past year a Portuguese named Bruno has brought creativity, inspiration and flair to an arena where we had become accustomed to see slow, staid and sleepily conventional performances. No, I am not speaking of Bruno Fernandes’ impact at Old Trafford, but Bruno Maçães’ impact on the European public sphere.

I have to admit that when I picked up Maçães’ book “History has begun”, it was with the suspicion that he was something of a charlatan. A European Tom Friedman spouting banalities like “The World is Flat” and other prophetic pronouncements perfected for the slick format of a TED talk or Davos panel.

How wrong I was. Maçães is no (in Talebian terms) Intellectual Yet Idiot at all. Rather the antidote. “History has begun” is one of the most interesting, refreshing and reflective geopolitcs books I have read in a long time – especially interesting on the increasingly blurred lines between fact and fiction as well as the increasingly diverging paths of the American and European continents – and has convinced me I will have to read his prequels “The Dawn of Eurasia” and “Belt and Road” as well. Even if you disagree with Maçães’ upbeat case for a bright American future, the book is thought-provoking and definitely worth reading.

In the course of the Covid-19 pandemic Maçães has become one of the main Twitter accounts I turn to for hot takes on the turn of global events. He has been a pertinent observer of the vaccine wars and (in spite of past allegiances as Portugal’s Secretary of State for European Affairs) a vocal critic of the EU’s bungled vaccination roll-out.

In a recent piece Maçães argues that the pandemic is finally ushering in the Great Acceleration that technology optimists have been waiting for since the collapse of the Dotcom bubble.

Maçães starts off in agreement with the Cowen/Gordon premise that we find ourselves in a Great Stagnation, from which only a major societal shock can shake us off and unleash the next leap in economic growth.

The question is if Covid is the requisite shock to kickstart the future? This is where I believe Maçães overplays his hand.

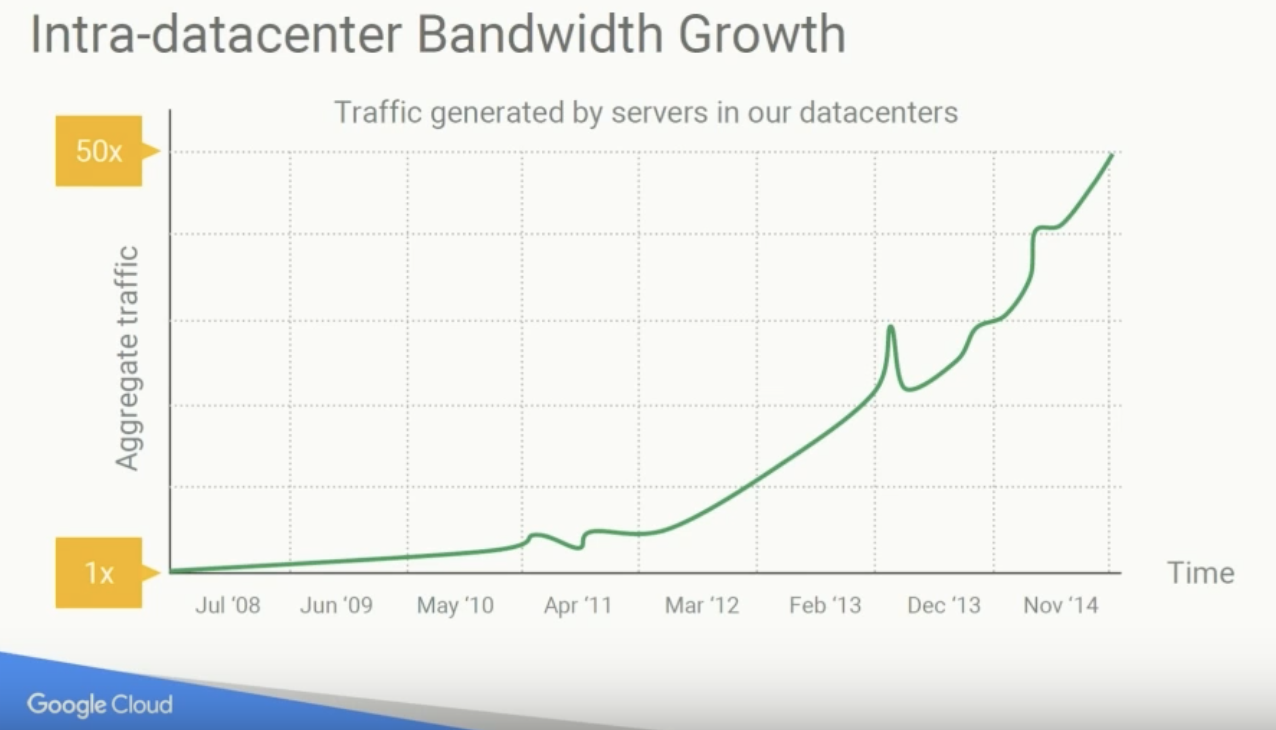

There is no doubt that the pandemic has led to an unprecedented burst in digitisation, that would otherwise have taken many more years to pan out. But the growth and (un)employment implications of this accelerated shift from physical to digital remain far less clear. Yes, the future has become more evenly distributed, but it has not necessarily become faster.

Maçães argues that “we have realised that time is actually scarce” – though it is unclear if the EU has reached the same conclusion. It is true that vaccines have been developed quite fast – thanks in part to government programmes such as the Trump administration’s Operation Warp Speed. And in the UK the government’s Vaccine Taskforce led by venture capitalist Kate Bingham (who was much mocked upon being given the post) has showed public/private partnership at its best and most effective – an exceedingly rare phenomenon in modern times.

The pandemic league of nations table looks very different today from one year ago. Back then the US and the UK were derided for being to slow to react to the spread of the virus, whereas the European countries promptly locked down their societies. But while the US and the UK failed in the early phase of the pandemic, they did so for the right reasons – putting a higher premium on the preservation of liberty than continental European or Chinese politicians tend to.

Now the tables have turned. The same higher risk-willingness that made the US and the UK slower to react to the pandemic, is enabling them to escape from the pandemic faster, whereas the risk-averse EU has been left miles behind in the vaccination race.

So Maçães’ claim that “[w]e tend to be more open to risk and disruption when they are present all around us, and the success of the new vaccines is making everyone more positive on technological development and its obvious achievements,” must probably be qualified. Yes, that might be true for the Anglo-Saxon countries, it seems less true for the EU bloc.

To me the pandemic illustrates the logic of a new world order where a post-Brexit Britain forms closer ties with the US and the other Five Eyes countries in a dynamic and entrepreneurial Anglosphere, whereas the EU likely will turn itself into an increasingly insular Neo-Napoleonic empire whose delusions of grandeur will be challenged by the hard realities of economic decline. Certainly, the election of the anti-British Joe Biden was a shot across the bow for a tighter “special relationship” between the US and the UK, but the logic of this concept will outlive Biden.

Maçães cites Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley investor who (like several others for different reasons) has labelled 2020 as the new year 0:

“I keep thinking the other side of it is that one should think of Covid and the crisis of this year as this giant watershed moment, where this is the first year of the 21st century. This is the year in which the new economy is actually replacing the old economy.”

There is truth to this. But it needs to be qualified. While the pandemic has undisputably accelerated digitalisation, few if any truly novel technologies have emerged in its wake. One much-touted hypothesis at the outset of the pandemic was that the closing down of societies would unleash a creative explosion. That may still bear out, but so far this prediction has been as wide off the mark as the prophesy of a covidian baby boom. Maçães mentions the usual examples of progress in AI and autonomous vehicles, but have these developments truly been accelerated as a direct result of the pandemic? Or just progressed at their usual pace regardless of it? I would bet the latter.

In fact, the economic consequences of the pandemic that have solidified at this stage are all rather bleak. At the national level the balance of power between China and the Western countries has shifted by leaps and bounds in China’s favour; At the corporate level the oligopolistic market dominance of the tech giants (the FAANG’s of the world) has reached unprecedented levels, at the expense of small- and medium-sized businesses; and at the citizen level the gap between the haves (who have enjoyed a comfortable countryside pandemic) and the have-nots has become ever-wider.

Maçães also touches on Bitcoin, which started its parabolic rise in the wake of the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus measures governments instituted to combat the economic fallout of the pandemic. While I certainly agree with Maçães that the cryptosphere holds great promise – I would go so far as to say the last hope for another economic revolution – it is worthy to point out that the founding premise of Bitcoin was not particularly optimistic. On the contrary, the inception of Bitcoin provided an escape valve for those who had lost hope in the system that collapsed under the financial crisis of 2008/09 – a monetary equivalent to the misfits who gave up and left a dystopian future in the old world for a Utopian future in America. And yes, indeed the price of Bitcoin has reached stratospheric levels, but that is not reflective of investor belief in a bright future. It is reflective of a world with a dearth of productive investment opportunities and where the real yields on bonds are ridiculously low and the (negative) real yields on cash even worse.

The ghost of a long-dead thinker whom Maçães quotes has come back to haunt us: Carl Schmitt, the crown jurist of the Third Reich, who has been made relevant again by the politics of pandemic. In the Schmittian playbook a pandemic provides ideal conditions – a state of exception – for wannabe Dictators to make their move. Be it more explicitly as a Putin or an Orban, who do not even care to hide their motives, or more subtly by democratic governments who dress up their emergency power grabs with assurances that they are for the public benefit and are only temporary in nature.

Perhaps it is not a great acceleration of technology we have in store, but a great acceleration of authoritarianism. Or, as certainly seems to be the case in China, a great Orwellian cocktail of tyranny and technology. Maçães tries to take a more upbeat spin on the Schmittian threat, by saying that: “The way to prepare for the emergency is to develop our powers of reaction well in advance”. That sounds fine in theory. But even in supposedly well-organised and advanced countries like my native Norway, the government has made a complete mockery of preparedness planning, despite being specifically warned of heightened risk of a pandemic in advance. Now I do not believe that Erna Solberg will turn Norway into a Dictatorship, but that is more due to the fact that politicians like her tend to respect democratic norms, rather than waterproof institutional safeguards against executive overreach.

Despite falling well short of Dictatorship in any meaningful sense of the word the emergency powers that “liberal” governments in many western countries have freely (ab)used, will be very hard to reverse and recover from. As Lord Sumption has made the probably most eloquent and principled argument for, “we cannot switch in and out of totalitarianism at will. Because a free society is a question of attitude, it is dead once the attitude changes”.

My hunch is that Maçães tries to be more positive than he actually is. His case for optimism seems somewhat forced, (more like Bruno Fernandes on one of his few uninspired days) and slightly at odds with the scepticism of his Twitter feed.

Even if we can finally see light in the end of the Covidian tunnel, the political situation, in the EU especially, can still get far worse from here. There is no way back to the status quo ante. Exception is the new normal. With populations suffering from Covid fatigue the last mile of the pandemic will be the longest. On the technology front we will wait for the promised acceleration to show up in the productivity statistics, which there is hitherto little sign of.