Democracy has long been hailed as the pinnacle of political systems, but perhaps it’s time to reevaluate this assumption.

“Democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time”. For three-quarters of a century, Churchill’s famous maxim has been invoked to shut down any discussion and debate about the merits of alternative political systems. While his quote seemed unquestionable for a long time, history may no longer be on his side.

The Western Triumph

Churchill’s remark, delivered in the aftermath of World War II, seemed justified as Western democracies emerged victorious against the anti-democratic forces of Nazi Germany, and as Stalin rung down the Iron Curtain from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, dividing the autocratic and communist Eastern Bloc from the democratic and capitalist West.

The subsequent decades further solidified the belief in democracy’s superiority over totalitarianism. The Western countries’ blend of democracy and capitalism increasingly appeared as a winning recipe, compared to the Soviet Union’s stale combination of communism, planned economy, Gulag and poverty. When the Cold War ended with the fall of the Soviet Union, it implicitly marked the ultimate triumph of democracy. The story had reached its end — as Fukuyama and other gleeful liberal professors would have it.

But hubris took hold. Riding high on their own success, the Western powers, led by America, embarked on ill-fated crusades to export their supposedly universal values of democracy and human rights to all the illiberal corners of the world. Korea, Vietnam, the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria. With very little success, it must be concluded in retrospect — with the jury still being out on the latest adventure in Ukraine.

The Chinese Challenge

Meanwhile, China quietly transformed itself into an economic powerhouse, leaving the Soviet Union’s stagnant economy in the dust. The rise of China as a manufacturing and technological juggernaut has challenged Western assumptions of their inherent supremacy.

Having been preoccupied with spreading democracy abroad, Western elites allowed democracy to rot at home, and turned a blind eye to this new threat arising in the East. China today presents an existential challenge to the liberal democracies on a completely different level than the Soviet Union ever did. Already in the 1960s, the Soviet Union’s economic stagnation was a fact. Khrushchev could threaten the West with missiles and shoe-banging rhetoric, but the quality of Russian cars, kitchen appliances and television sets was nowhere near matching the standard of their western counterparts.

Today there are few things the Chinese are not making better than us Westerners. Since Deng Xiaoping’s late 1970s reforms, China saved, studied and invested, strategically transforming itself into the factory of the world, whereas the West became decadent, offshored its manufacturing production, outsourced its know-how and indebted itself to finance mass consumption and mass immigration at home.

The re-integration of China and the Eastern bloc into the global economy contributed to a global savings glut that sent interest rates to historic lows. Alas, the Western democracies could not resist to abuse this opportunity. One of the greatest ironies of the last 50 years is that the savings of poor Chinese with a low time preference financed the overconsumption of affluent Westerners with a high time preference.

Previously, the notion persisted that China produced only inexpensive hardware, with the West leading in design and software. However, this changed with TikTok’s emergence as a transformative platform. Western youth adopting Chinese social media like TikTok over Western alternatives signifies a paradigm shift. Similarly, Elon Musk’s aspirations for Twitter (now X) to emulate WeChat – the Chinese “everything app” – highlight China’s increasing technological influence. China has transitioned from imitating the West to being emulated by it. China has gone from copying the West, to being copied by the West.

Consequently, Chinese wolf warriors have become much more assertive vis-à-vis the West in recent years. Whereas it is doubtful that anyone but the most ideologically blinded of Communist apparatchiks ever truly believed that the Soviet system could deliver better living standards for Soviet citizens than the capitalist countries, the Chinese propagandists are openly challenging the presumed supremacy of the Washington Consensus. Sure, China’s GDP per capita remains only a fraction of those in OECD countries, but the gap has been closing precipitously. And with 1,35 billion inhabitants, that means that several hundred million Chinese are already enjoying living standards comparable with or even superior to those of Westerners. That is a marked change from the Maoist era when even the top party brass suffered under poorer living conditions than average workers in the West.

But China is not exactly a paragon of civil liberties, one might logically interject. True. If a Chinese citizen has the temerity to compare great Chairman Xi to Winnie the Pooh for example, he would have to dispel any notions of habeas corpus or rights to a fair trial and be prepared to rot in a prison cell as long as the regime deems necessary for the harmony of the kingdom. If a billionaire who has spent too much time in the West starts to make politically problematic statements, his body will disappear along with his fortune. Perhaps in a few years’ time his body, stripped of its former personality might re-appear to express deep contrition for wrongs committed against party doctrine, but his wealth will have been distributed to more pliable comrades. And don’t even think of mentioning the one or two million Uyghurs who have been enslaved in concentration camps in Xinjiang province and subjected to everything from intense surveillance to forced labour and involuntary sterilisations. If we are to take the Party line, as expressed by the governor of the province, at face value, these 380 re-education camps either do not exist or the Uyghurs have “graduated” from them.

The Covid Challenge

When the Covid-19 pandemic struck the CCP decided to extend its Uyghur policy nationwide. Across the Middle Kingdom people were universally being enclosed in their apartments, in the most draconian lockdown the world has ever seen, courtesy of the 21st century surveillance system the sinister Orwellians of the communist regime have devised and implemented to perfection. It offered little relief for the Uyghurs, except perhaps in the sense of equal treatment with their fellow citizens.

The Chinese lockdown presented a glittering opportunity for the West to showcase its unique value proposition differentiating it from the despotism of the Orient: an open society. What a pity then that the democratic governments of the West decided to copy the totalitarian Chinese pandemic policies, lock, stock and barrel, throwing all the principles of liberty and freedom out of the window.

With the benefit of hindsight we know that the coronavirus was not nearly as severe as the Black Death or the Spanish flu. Nobody could know that at the time however, so Nassim Taleb and others invoked the precautionary principle in favour of instituting mediaeval-style curfews to stop the working classes from going about their daily business and spreading the virus to colleagues, friends and family. At first not much happened as governments hesitated in the face of this unfathomable foe. It took the morbid scenes emerging from the morgues of Lombardy to whip politicians and plebeians alike into a state of panic. Like clockwork, Western capitals began shutting down their societies in the gloomy days of March 2020.

People who cite the precautionary principle always sound very clever, perhaps too clever by half. It is a hard principle to argue against. But it was not the principle Western civilisation was built on. Yes, Covid could have been more deadly. But shutting down societies is not risk-free either. We still don’t know the long term collateral damage from the lockdown years.

In the rush to beat the virus, executive powers were abused, constitutions were forgotten and fundamental rights of a free society were infringed. Lord Sumption has fittingly described this “radical experiment” as a “complete failure of government”. The principal problem, as Sumption put his finger on, is that once an open society relinquishes the very freedoms and liberties that made it an open society, there is ipso facto no possible path back to the status quo ex ante. The spell is broken. No more than eggs can be unscrambled or Eve could have unpicked the forbidden fruit, can freedom be fully restored to its original when the threat of it being arbitrarily taken away is not only theoretical but lies implicit in the historical precedence. The formerly unthinkable has become repeatable.

It will remain a riddle, wrapped in mystery why the Western governments decided to base their pandemic policies on coercion and not on volition. In doing so the British government, for example, acted in direct contradiction of SAGE, its panel of expert scientific advisers, which advised that: “Citizens should be treated as rational actors, capable of taking decisions for themselves and managing personal risk”. Instead, the government chose coercion.

I won’t delve into the details of the UK government’s pandemic response, which, in my view, Lord Sumption has extensively and damningly criticised; how the Johnson government overstepped the powers vested in it under the Coronavirus Act and the Public Health Act 1984; how the courts did nothing to intervene; and how Parliament went into recess in the crucial months of March and April, and thereby effectively abdicating from its constitutional role as a check on executive (abuse of) power — an opinion seconded by retired Supreme Court president Lady Hale.

While many Western countries adopted the Chinese pandemic policy template, it is bemusing that the most ancient of the European democracies, Britain, along with its colonial offshoots Australia and Canada, went to the extreme of resembling a police state with stringent and even unreasonable lockdown enforcement.

It is also not without irony that Donald Trump would more likely have won re-election in 2020, if he had embraced more authoritarian lockdown measures and become the tyrant his critics promised he would be but which he ultimately did not become. Instead he stayed true to his freedom-loving instincts and lost.

In the UK Boris Johnson’s downfall was both deserved and self-inflicted. On the one hand it is absurd that a prime minister should be forced to resign for having enjoyed cheese and wine with staff in No. 10. But he was the one who made these absurd rules and restrictions on social gatherings that he expected his voters to follow but could not comply with himself. He is now relieved of political duties and free to cash in on the speaking circuit, hobnobbing with plutocrats and potentates.

His political legacy might have fared better had he not chosen to lock down the kingdom and instead focused on delivering Brexit. If he had surrendered to the virus back in March of 2020 that could even have given him the tragic death of one of his favoured Greek heroes, instead of the highly lucrative but dishonourable way he now leads his life.

The lone holdout of common sense throughout the pandemic was Sweden — which might come as a surprise given that common sense has not been in high supply in Sweden the past few decades. The answer might be because it was not the democratically elected government that was running the show, but a technocrat. Anders Tegnell, the state epidemiologist, at times seemed to fight a one-man battle to keep Swedish society open. Against the forces that wanted to shut societies down. The media made him an object of ridicule. The governments of other countries tried to shame Sweden into submission. The hapless Löfven government effectively went into hiding, preparing to sacrifice Tegnell as its fall guy. Still, Tegnell refused to budge to the orthodoxy of the day.

I visited Stockholm during the pandemic. The streets and restaurants were certainly less crowded than they would normally be. The Swedes were obviously taking the virus seriously. The only difference was that Tegnell trusted his countrymen to make the best decisions for their own self-interest, rather than using the coercive powers of the state to order people to act in the interest of the public health service. Here it is worth remembering that the original purpose of having a public health service is to protect the population. But what the pandemic revealed is that this concept has been turned on its head in most Western countries; the health service must be protected from the people — as exemplified by the Johnson government’s Orwellian slogan: “Stay Home, Protect the NHS, Save Lives”.

Sweden did suffer higher excess mortality than the other Scandinavian countries in the early stages of the pandemic, mainly due to deaths in homes for the elderly. But in the end Sweden fared no worse but better than the European average in terms of covid death rates per capita, and significantly better than both the UK and the US.

More importantly, the Swedish experience demonstrates that it was not only wrong and possibly illegal to lock down society, but unnecessary. In the words of Talleyrand, it was worse than a crime, it was a blunder. Tegnell did not have the benefit of hindsight anymore than other Western leaders. And he was of course as mindful of the precautionary principle as anyone else. What separated him from the others was that he had the wisdom to confront a then unknown enemy without an unproportional use of the coercive powers of the State.

Tegnell was much vilified, but ultimately vindicated. Other Western governments however, were so fearful of overburdening their public health services that they were willing to sacrifice the open society.

Aristocracy in theory, Mediocracy in reality

Thomas Jefferson envisaged democracy as true aristocracy. Government by the best and brightest, decided on merit, not by birthright. It was a fine idea in theory, but a quarter of a millennium later we have to conclude that it has come way short of promise in practice.

Jefferson might not have been surprised. After all, the founding fathers were battle-hardened men and not nearly as naive as the liberals of today. They shared a certain pessimism about the long-term prospects for democracy. Jefferson’s predecessor, John Adams, never expected democracy to last long. “It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide”. Jefferson himself quite darkly remarked that: “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure”.

Jefferson wanted meritocracy. What we have ended up with is mediocracy. Government not by the best and the brightest, but by the most mediocre among us. As the electorate expanded over time, the competence of the elected declined. Democracy promised leaders who are the first among equals, but ended up with politicians who are simply more equal than others.

In a bizarre perversion of Jefferson’s democratic ideal some, such as the Communist Norwegian member of parliament Mímir Kristjánsson, are even celebrating the fact that his fellow politicians have no merits or virtues distinguishing them from the average voter but that they are just as average as any random sample of the populace — as was demonstrated recently when the leader of the Red party was forced to resign after being busted for stealing a pair of Hugo Boss sunglasses.

There is also little to indicate that wider representation has led to wiser policy and better political outcomes. On the contrary, the great social reforms of the 19th century were instituted prior to the introduction of universal suffrage. In Germany it was not the socialists but Bismarck, the Iron Chancellor, who introduced State Socialism — providing health insurance, pensions, disability benefits, workers protection and restrictions on child labour.

Contrary to popular wisdom Victorian noblemen and Prussian Junkers did as much, if not more to improve the living conditions of the working classes than the organised labour movements, whereas the modern “Labour” parties have, as Spengler predicted, been effectively co-opted by the liberal bourgeoisie.

As H. L. Mencken commented a century ago, after hyperinflation had doomed the newfangled democracy of the Weimar Republic, but before the democratic allure of Nazism seduced the German nation into Götterdammerung:

“Since the abolition of the three-class system in Prussia there has been absolutely no improvement in the government of that country; on the contrary, there has been a vast falling off in its honesty and efficiency, and it has even slackened energy in what was formerly one of its most laudable specialties: the development of legislation for the protection of the working class, i.e., the very class that benefited politically by the change.”

Mencken predicted that democracy would not only be self-limiting, but possibly also self-devouring. He wrote his critique in the days of Wilson and Roosevelt. One can only imagine what he would have thought of Biden and Trump. He would hardly have been impressed.

It is not hard to see the 2024 US presidential election as the fulfilment of Mencken’s prophecy. The final showdown of a degenerate democracy. The senile representative of the stagnant status quo versus the buccaneering billionaire con-artist portraying himself as tribune of the plain people.

The majority of the electorate in most Western countries retains a blind faith in the merits of democracy. Yet, when moving from the abstract to the concrete, people have exceedingly low expectations for democracy’s potential to solve the actual political challenges facing society.

The kind of enlightened liberal debate that characterised 19th-century parliamentarianism now seems like a distant ideal.

The Debt Challenge

Living standards across the West today are higher than they have ever been. However, growth rates are stagnating, while wealth and income inequality have reached record levels. The degree of public immiseration is high and rising.

A prevailing outcome in modern democracies is the continual rise of debt ratios. Margaret Thatcher said that the problem with socialism is that eventually you run out of other people’s money. The problem with democracy is that you eventually run out of people to borrow money from.

In the US, for example, one of the few points of agreement between Republicans and Democrats is the acceptance of permanent deficits.The size and complexity of the modern state combined with extreme levels of political partisanship means that the scope for Congress to enact required reforms is near zero. Republicans will cut taxes where they can and Democrats will raise spending where they can. Congressional horse-trading often yields half-baked measures that add costs and complexity to an already oversized state, without addressing underlying political issues. If ever a bill is introduced that reduces complexity and cuts costs, it has zero chance of passing both houses of Congress and being signed into law by the President. And so the debt clock keeps ticking.

US government debt has now risen to 32,7 billion dollars — an astounding 119 percent of GDP (the federal debt that is, not counting state and local debt, which would bring the total to 132 percent of GDP). This debt ratio is more than double the level recorded at the beginning of the millennium. The Euro area is little better, at 91,6 percent of GDP (at the end of 2022), with the UK in between at 115 percent of GDP, (also at the end of 2022).

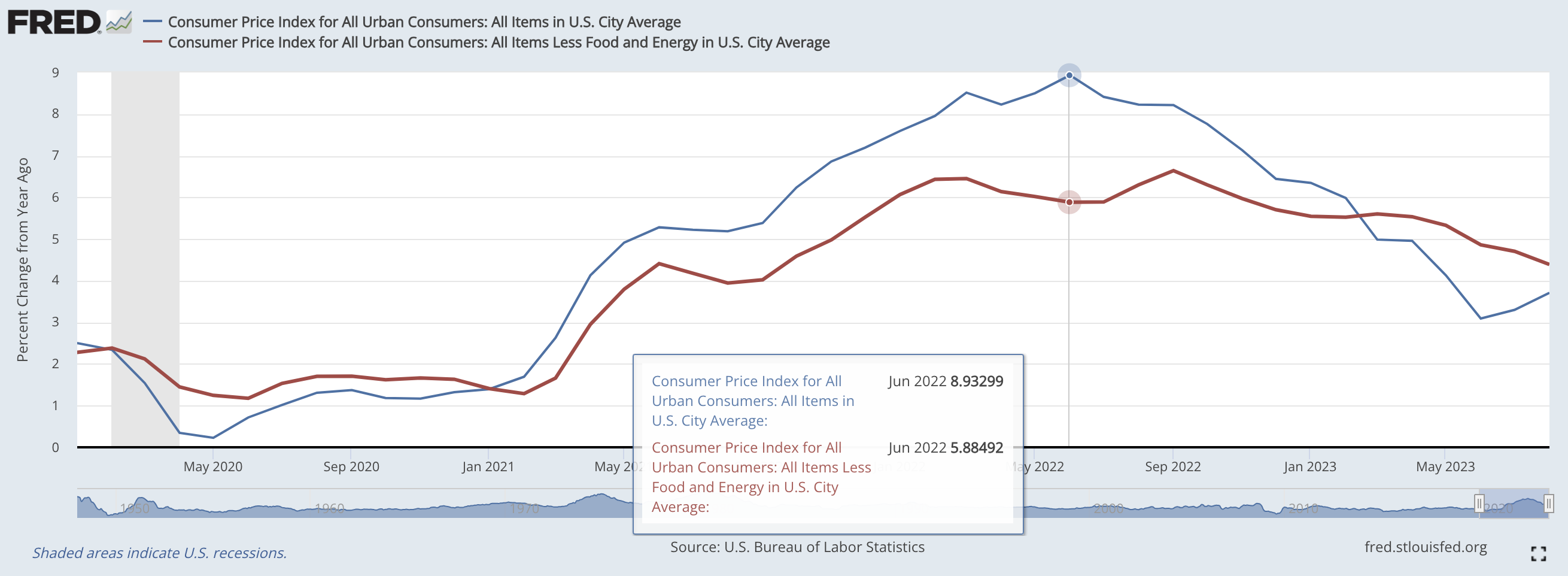

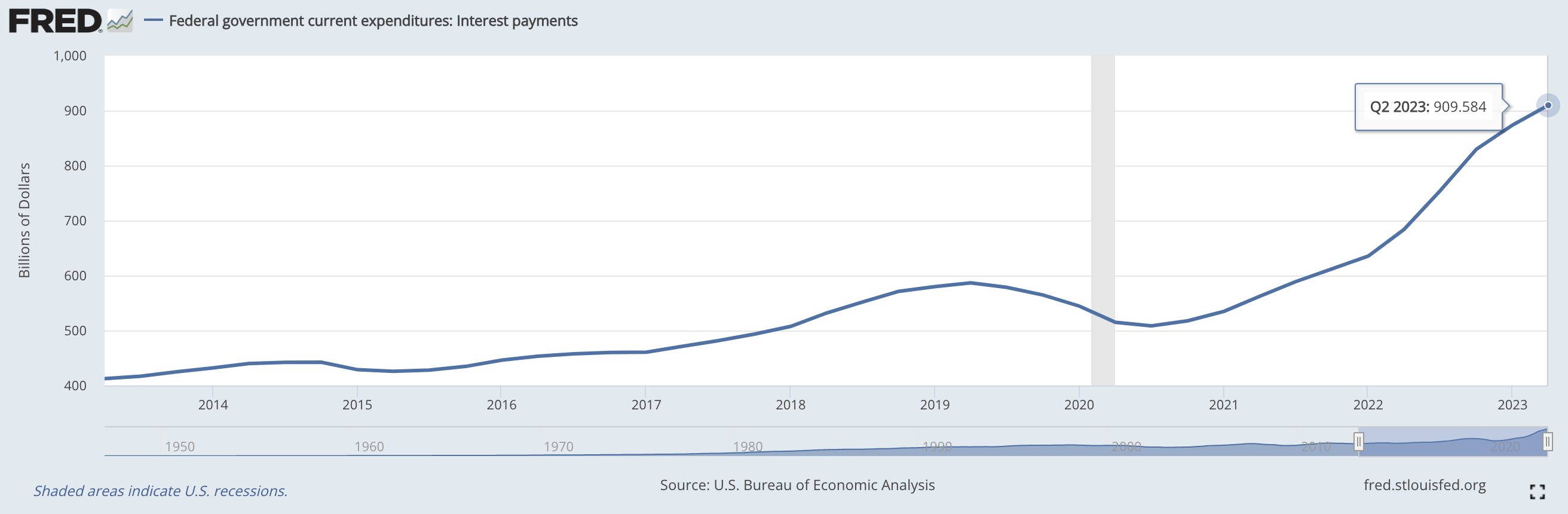

More worryingly, interest expenses are accelerating even faster than the debt outstanding. Interest payments on the federal debt amounted to a record 475 billion dollars in fiscal year 2022, a 35 percent increase from the prior year. It will increase even more this year.

During the second quarter, federal interest expenses nearly reached one trillion dollars on an annualised basis. That is a tripling of federal interest expenses in three years. Let that sink in. US politicians have not yet.

I might be overemphasising a single book, yet I suspect that the book on sovereign debt crises by Ken Rogoff & Carmen Reinhart published after the financial crisis had unintended and unfortunate consequences. The authors identified a 90 percent debt to GDP ratio as the threshold where economic growth would start to slow and the risk of a debt crisis increase. The book became widely influential, until somebody came along and found errors in Reinhart and Rogoff’s spreadsheets, apparently debunking the whole thesis that debt imperils growth. Even if the authors made some mistakes that perhaps led them to oversell the 90 percent threshold as the crucial line in the sand, the overall thesis was sound. To conclude that debt does not matter much would be misguided, but unfortunately that became the moral of the story — certainly for politicians.

Democratically elected politicians are simply not taking debt seriously. And why should they? They will be out of office — and richly rewarded by the special interests they represented — long before the debt comes due. Spiralling indebtedness has thus become an inherent characteristic of democratic systems. As a mode of government democracy inherently has a high time preference, prioritising the present over the long term. Only politicians with a high time preference can succeed in a democratic system. Never has a political candidate won an election on a platform to reduce the national debt. For parliamentarians or presidents serving 4-year terms, it is always more politically expedient to assume that the issue of public indebtedness can be deferred to their successors.

But can this can be indefinitely kicked down the road? Perhaps it can. After all, it has sort of worked so far. But it would not be safe to bet on. The only safe bet is that the democratically elected leaders of the West will persist in happy-go-lucky deficit spending, hoping that the threat of sovereign debt crises will not materialise on their watch.

Democratic Denouement

The zenith of democracy has passed. It has been a pretty good run, but now it has reached a dead end at last. The West is getting old and tired and so is our cherished political system. European civilisation experienced rebirth once before, but given the current demographic profile, another Dark Age seems more likely than a new Renaissance.

Western populations live more affluent lives than ever before. But that is more in spite of than because of anything the democratic process has contributed over the last half century or so. I would argue that democracy achieved peak performance when it was practised in a more limited form in between the Napoleonic wars and the First World War, when reasonable debate could and did lead to reasonable reforms, and the State did not intrude too much with man’s march of progress. In our day democracy has become a parody of itself.

China is the biggest challenger to the democratic world. Impressive as the rise of the Middle Kingdom has been since the Communist party finally stopped starving and butchering its people on a grand scale after Mao passed away, it is unlikely that Chinese GDP per capita levels will ever catch up with the West. It even remains uncertain whether the Chinese economy will surpass the US as the world’s largest economy, as long predicted, according to some as early as 2026, (measured at market exchange rates).

As such the bigger challenge for the democratic countries might come from smaller city states such as Singapore and Dubai, which are already giving the West a run for the money in the GDP per capita league tables. These city states have combined Oriental despotism and Western free-market capitalism in a way that has proved remarkably successful. The only metric they are scoring low in is democracy. Which begs the question: does a democratic system of government hold inherent value if it fails to produce better outcomes for a society than enlightened autocracy? Westerners might be biased in favour of democracy, but it is doubtful that the populace of Singapore would have traded the economic miracle under Lee Kuan Yew for free and fair elections that would have left it as impoverished as the rest of Malaysia.

I was indoctrinated in school to believe in democracy, not to question it and to consider no alternatives. Perhaps that is part of the reason why the system has become so sclerotic. People in the West have continued to sing the praises of democracy and bombed our universal Western values on the rest of the world, metaphorically and literally. But we have not challenged our own system. Jefferson’s tree of liberty has not been refreshed in a long time. Is democracy still the least bad form of government among all those attempted? This question demands renewed examination. The hypothesis should no longer be accepted on faith alone. If democracy shall stand a chance to revitalise itself it must be questioned and challenged.