The Google system of the world is an evil empire that stifles entrepreneurial activity and is doomed to fail, before a decentralised Internet will rise from the ashes, argues George Gilder in his latest book.

On the face of it the main argument George Gilder is making in his latest book is preposterously bold: “The Google era is coming to an end because Google tries to cheat the constraints of economic scarcity and security by making its goods and services free. Google’s Free World is a way of brazenly defying the centrality of time in economics and reaching beyond the wallets of its customers directly to seize their time.”

Considering that Google generated revenues of 136,8 billion dollars and profits of 30,7 bUSD in 2018 and has a market capitalisation not far shy of a trillion (870 bUSD as of April 22), its decline and fall does not seem imminent, but a rather far-fetched prospect.

Google’s system of the world

Google is not only one of the most valuable (on some days the most valuable) companies in the world, but more than any other of the tech giants Google represents a system of the world, (borrowed from Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle trilogy). A system of the world necessarily combines science and commerce, religion and philosophy, economics and epistemology.

Google’s theory of knowledge, its religion, is Big Data. Whereas good Christians may go to heaven “good googlers” are on a determinist path to a place called Singularity, where technology has transcended biology and artificial intelligence surpassed human intelligence.

Reaching Singularity rests on two conditions:

- All data in the world can be compiled in a single “mind”.

- Algorithms sufficiently comprehensive to analyse the data can be written.

As Gilder points out the Google theory of knowledge and mind are not mere abstract exercises. They are central to Google’s business model, which has progressed from “Search” to “Satisfy”. Google can already show considerable evidence that with enough data and processors the search engine can know better what will satisfy your longings than yourself. Notwithstanding that it in many cases makes us stupider: Just last weekend I was in Vienna and Google could tell me a restaurant I fancied was closed for lunch. We walked by to double-check and lo and behold open the restaurant was.

The fatal conceit of Google-Marxism

Gilder – an unreconstructed Reaganite free-marketeer – sees Google’s idea of a universal omniscient logic machine as deterministic and ultimately dictatorial. He accuses Google of repeating Karl Marx’s erroneous belief that we have reached the final stage of history. An immanentized escathon, in the words of William Buckley. Ironically both the technology Utopians and Dystopians share the belief/delusion of the coming all -powerful AI. Gilder thinks they are exaggerating the attainments of their own era, and sees the gospel espoused by the Google guys, Ray Kurzweil (since 2014 employed by Google) and the likes of Life 3.0 author Max Tegmark and Yuval Noah Hariri as hubristic Google-Marxism. Gilder accuses the AI champions of being blind to the realities of consciousness and of having forgotten Gödel’s lesson that all logical systems, such as AI, is incomplete and in need of an “oracle” (such as human consciousness outside the machine). He does not share Kurzweil’s position that when a machine is fully intelligent it will be recognised as conscious.

Indeed, there are eerie similarities between the Google theory of progress and the Soviet economic theories of central planning. The Soviet economist Leonid Kantorovich, who won the Sveriges Riksbank’s economics prize in 1975, the year between Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, never shed the belief that advances in information technology would give Gosplan (close to perfect) knowledge and make central planning more efficient than market choices.

One foundational feature of the Google system is the Zero Price. Informed by Internet pioneer Stewart Brand’s slogan that “Information wants to be free”, Google has made (almost) all of its content and information free, in a digital version of the medieval Commons – i.e. public resources available to all. Private data are the mortal enemy of the Google system of the world.

In Gilder’s view the Zero price is the fatal flaw that dooms Google, just as Hayek predicted that the lack of price signals would doom the Soviet economy. Jeremy Rifkin heralds a Zero Marginal Cost Society, where prices for near every product and service will reach (close to) zero as every device and entity become connected in an Internet of Things and exponential network effects will unleash a Utopia of leisure and abundance – (a vision for the future that needless to say is much in vogue at the Googleplex).

Gilder does not buy into that prophesy. He sees “free” not only as a lie – as Apple CEO Tim Cook acerbically pointed out: “If the service is ‘free’ you are not the customer but the product” – but as a return to the barter system, a system so inefficient that it was left behind in the Stone Age: “Above all, you pay in time. Time is what money measures and represents – what remains scarce when all else becomes abundant in the “Zero Marginal Cost” economy. Money signals the real scarcities of the world concealed in the false infinities of free.” Furthermore, “free” entails a slippery avoidance of liabilities to real customers and no concern for security.

Disconcertingly for Google there are many signs that internet users have had enough of attention-grabbing ads and lack of data privacy.

- Adoption of ad-blockers are skyrocketing to the degree that even Google itself has felt forced to launch their own “ad-blocker” – and it is the most attractive demographics for advertisers that are leading the trend. In the US 25 percent of internet users were blocking ads in 2016.

- Internet users are simply developing “banner blindness”, becoming more or less immune to the bombardment of ads.

- In the product-search category Google is rapidly losing ground to Amazon. Internet users still prefer Google for informational searches, such as “What is the capital of Kazakhstan?”, “Was Jesus a Muslim?” or “When will the world end?”. But by 2017 Amazon had captured 52 percent of the product-search market; intentional searches for products to buy, vs 26 percent for Google and other search engines.

Nobody really wants the value-subtractive ads that are the underpinning of the Google system. Gilder, who is 78, thinks this will doom Google within his lifetime, although he qualifies his prediction by saying that search will likely remain a valuable business.

Crashing into Hölzle’s Wall

If you meet any technology investor today his first question will likely be if your business is “scalable”? Meaning if you are able to grow revenues with less than proportional, or ideally no increases in marginal cost – the key to ever-fatter profit margins. That is what the likes of Google and Facebook have achieved, and what investors hope the likes of Amazon, Uber, Spotify, AirBnB et al. will achieve.

The question is if the margin story can continue for Google? An inherent challenge in Google’s business model is that “free” inevitably leads to over-consumption. “Free” has enabled Google to capture (effectively) the entire market, but will the company eventually collapse under the weight of the unlimited demand for its free services? As Gilder writes: “The nearly infinite demand implicit in ‘free’ runs into the finitude of bandwidth, optical innovation, and finance – a finitude that reflects the inexorable scarcity of time. This finitude produces not zero marginal costs but spikes of nearly infinite marginal costs – Hölzle’s wall. The latter a reference to Google employee number 8, Urs Hölzle’s lament that Google’s cloud infrastructure was “rapidly approaching a wall”.

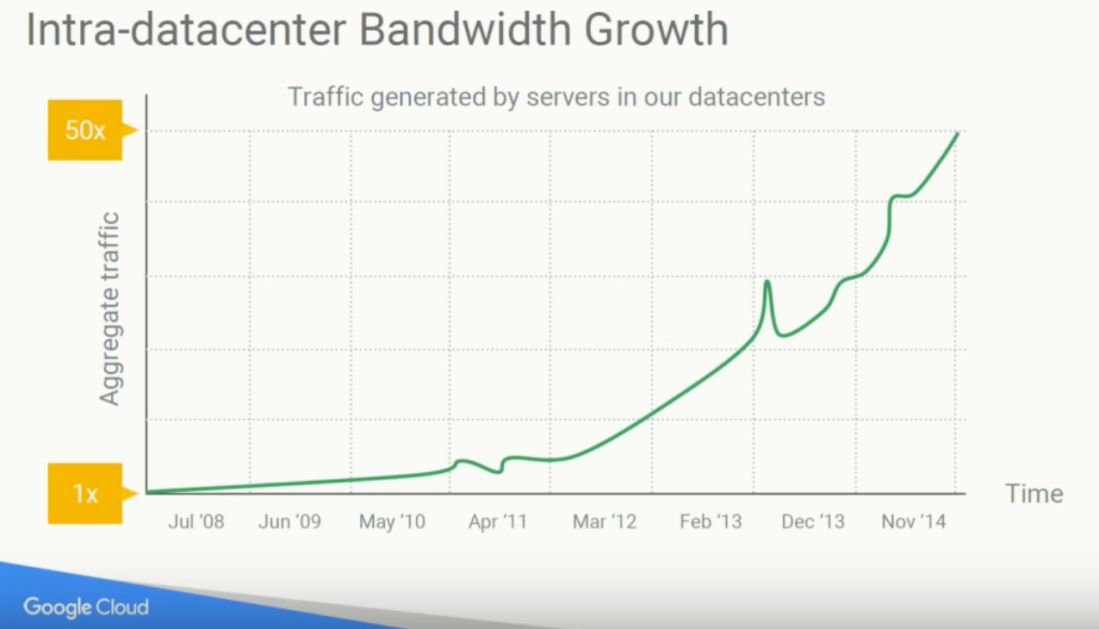

The exponential growth in demand for Google’s services (see chart below) – which roughly doubles every year – has forced Google to build out the largest cloud infrastructure on the planet over the past 15 years, with three underwater cables across the Pacific and more on the way. The 12.899km third cable from California to Hong Kong (that was scheduled to be completed last year but is delayed) will carry data at a rate of 144 terabits per second – up 29-fold from Google’s first 5tbps cable from California to Japan in 2010.

This is putting huge Capex pressure on Google, with the need to continue building massive data centres and undersea cables. As Hölzle pointed out in his 2017 keynote apart from the change from copper to fibre, cable building has not changed much over the past 150 years and the system’s reliance on a small amount of cables leaves it vulnerable to tail risks. Still, Google is to a significant degree essentially free-riding on the backs of carriers such as AT&T, Verizon and T-Mobile, whose infrastructure investments Google is totally reliant on. The cost is ultimately passed on to the end user: On average (US) smartphone users pay 23 dollars per month for ads, trackers, scripts and other spam that strikes them with malware, slows load times and depletes battery life. Strikingly, on popular publishers’ sites as much as 79 percent of the mobile data are adds.

What will replace the Google World Order?

The latter parts of Gilder’s book are somewhat unstructured and anecdotal but contain insightful observations. Obviously, it would be a futile exercise to foretell exactly how the Google system will meet its end. But Gilder argues interestingly that the overarching threat to Google will come from the Cryptosphere. That the un-secure and centralised Google Empire will be replaced by a decentralised and secure Crypto order. That is admittedly far away – 70 percent of all Internet links are handled through Google or Facebook. But alternatives are emerging, such as Blockstack, whose mission is to “foster an open and decentralised Internet that establishes and protects privacy, security and freedom for all internet users.” Tim Berners-Lee, who fears the Internet is being broken by the centralisation of user data in the giant silos of Google, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft – is one Blockstack admirer.

Gilder also goes through the emergence of Bitcoin and Ethereum and discusses their potential and limitations as currency systems. He sees the upper limit of 21 million total bitcoin units as one of the main challenges that would likely be highly deflationary over time. The high price volatility of Bitcoin could likely be addressed by more issuance and circulation of Bitcoin-redeemable liabilities – something which SEC’s clampdown on ICOs and crypto in general may put up obstacles for. Nevertheless, despite all the challenges it is clear that it is in the Cryptosphere the most interesting economic and political ideas are to be found today.

In the “Googlesphere” on the contrary, true entrepreneurial activity is being stifled by the narrow focus on developing largely parasitic apps and profitless Unicorns inside the Google/Android, Facebook or Apple iOS ecosystems — (a charge I would stand guilty of myself). Gilder also laments investors excessive belief in Marc Andreessen’s mantra that “Software will eat the world”, which has the unfortunate effect of crowding out innovative hardware investment. Though there are pockets of light, such as Luminar Technologies, which manufactures advanced Lidar censors for autonomous vehicles. What makes Luminar founder Austin Russell stand out from the crowd is that he does not believe in the consensus that autonomy is chiefly a software problem, but a hardware one, and that no amount of big data, artificial intelligence and software can make up for bad data from hopelessly outdated hardware. In contrast for example, two of the three finalists in the startup pitch at the Web Summit in Lisbon before Christmas were self-driving startups focused on getting more out of existing hardware with better software, one of them even claiming that a $12 camera will suffice for self-driving – Luminar would beg to differ.

Most business books today are boring. Life after Google is definitely not boring. And even if Gilder will be proved wrong in his hypotheses about the fall of the Google system of the world and the rise of the Blockchain economy, his analyses are insightful as well as idiosyncratic. That makes the book worth reading for everybody seeking to understand the new and uncharted economic landscape we find ourselves in.