To paraphrase Mike Tyson and Harold Macmillan: In financial markets everybody has a forecast until events punch them in the face.

So, I am probably wrong but this is how I forecast that the situation in the bond markets will play out.

First a brief recap.

For the past year and a half the Federal Reserve—tasked with its dual mandate of price stability and full employment—has hiked interest rates aggressively to combat inflation, which had spiralled out of control following the pandemic. (I am firmly in the camp who believe inflation accelerated more as a result of the Feds massive money printing experiment rather than supply side constraints in the pandemic years. But leave that aside for now).

By all appearances the Fed (and other central banks) kept interest rates at the zero bound for too long, was too late to start hiking rates and could probably have front-loaded more of the hikes in a “shock and awe” way.

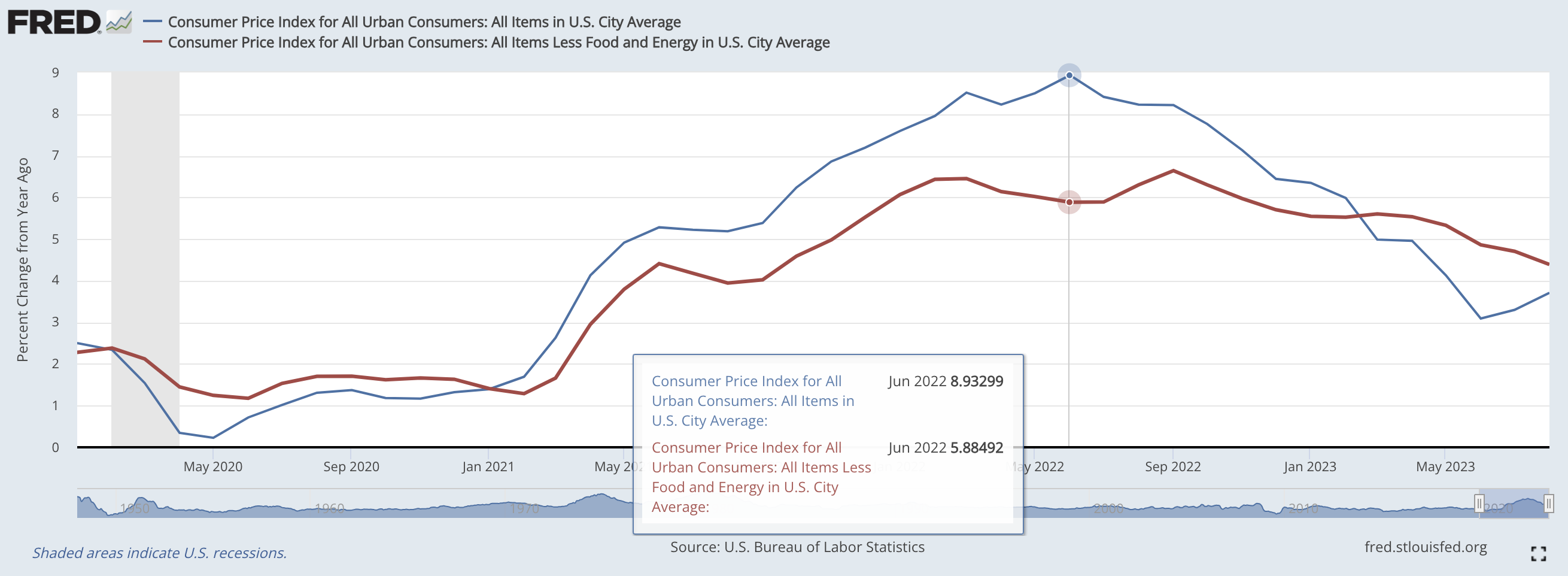

Whether the Fed is to thank or not, inflation has now decelerated quite a bit, from a high of 8,9% year over year in June 2022 to 3,7% in August, (somewhat worryingly up from 3,1% the month before). Somewhat disturbingly the core inflation rate is proving to be rather sticky.

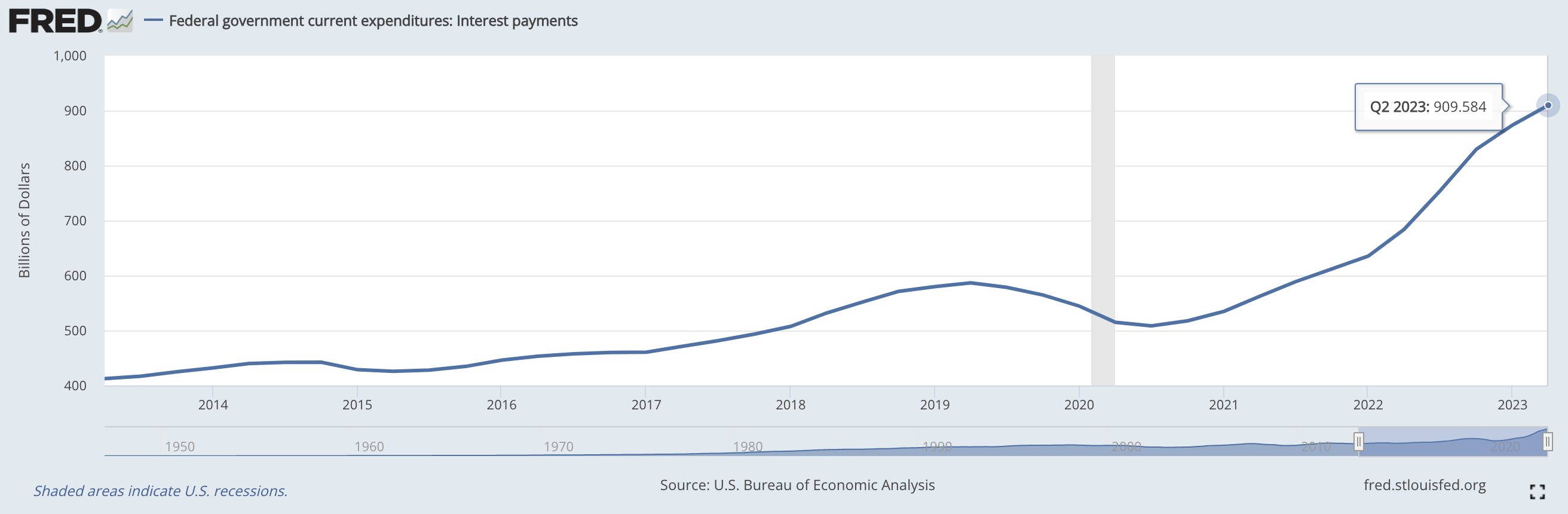

The problem for the Fed is that the lever it is using to control inflation, i.e. the interest rate, is causing severe collateral damage in the form of higher government borrowing costs—which is fast approaching an annual rate of one trillion dollars.

With the low average maturity of the US debt stock this might easily double again to two trillion dollars already in the next year or two. Running budget deficits at banana republic levels as far as the eye can see does not brighten the outlook.

These levels of interest expenditure are obviously not sustainable. The bond market seems to agree. Since the summer the yields on both 10- and 30-year Treasury bonds have increased at a brisk pace—to levels not seen since before the Great Financial Crisis—and talk about “bond market vigilantes” is suddenly all the rage again—always an ominous sign.

So, we have at the one hand the Fed approaching the end of its interest rate increasing campaign, as evidenced by plateauing rates at the short end of the curve. And on the other hand increasing rates at the long end of the maturity curve.

And voila, all of a sudden the interest rate curve is a lot less inverted than it was back in the summer a few months ago.

This is causing the warning lights to flash that a recession may be around the corner, or perhaps already here—the softening macro data of late does not rule that out. As bond investor Jeffrey Gundlach tweeted yesterday, it is time to “buckle up”.

My view is that we are at, or close to an inflection point. The curve will continue to de-invert and eventually steepen, as the economy slows down and the US Treasuries market starts to crack under increasing pressure.

The Fed itself forecast that the funds rate will come down smoothly and gradually over the next two years.

I don’t believe that will be the case at all. If history is any guide it never happens this way. The Fed never cuts interest rates smoothly and gradually. As soon as a real or perceived crisis hits the FOMC in the face, they panic and cut rates abruptly and steeply.

Just look at the chart, (the only possible exception was in the mid-90s).

The Fed is continuing to painstakingly talk the talk about “higher for longer”. The market has always taken this with a grain of salt, as evidenced by consistently pricing the implied future funds rate lower than the median forecast in the Fed’s own dot plot. The market only believes the Fed’s tough talk until something snaps. Then everybody knows that Jay Powell & co will chicken out.

So far the US economy has proved remarkably resilient in the face of rising rates. The banking crisis in the spring (with the fall of Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank) was a shot across the bow, but the Fed managed to contain the crisis quickly before any escalation to the wider banking sector.

The fact that nothing has broken yet, does not mean that it will not break eventually though. I believe a breaking point is fast approaching. It is impossible to foresee exactly how it will unfold. But the imbalances are piling up, to such a degree that it is hard to see how either government and/or household finances can withstand the pressure for much longer.

The Fed is struck between a rock and a hard place. The fight against inflation is far from won. But the medicine is proving to have too severe side effects for the indebted US government.

My belief is therefore that the Fed will cave before the war against inflation is conclusively won. The Fed funds rate will be slashed in half, not over the course of two years but in a matter of months.

When will that happen and what will the trigger be? That is of course impossible to say, and renders any advance analysis incomplete. But I will go out on the limb and predict that developments in the longer end of the bond market will force the Fed’s hand much sooner than the majority of market participant currently believe. I assume that Powell will try to find another pretext for his coming course correction, be it a soft employment report, another bank failure or a sudden stop in some obscure corner of the credit markets. But he will chicken out, sometime between here and before Easter next year, I hazard to guess.

It is not without irony. But the only thing that can save the US from a government bond crisis is a slowdown in the economy or a financial crisis that will give the Fed the pretext it needs to bail out the bond market.